Young America, like most of the world, was a segregated colony and country. That racial heritage has beleaguered our nation throughout its history, with deep rooted harm lasting even unto today. While Nantucket enjoys the relative peace and mutual tolerance and support characteristically found in many small, isolated communities, it is by no means immune and safe from the malady that is rife throughout our society. As the long overdue nationwide protests continue, it is natural to wonder if we can ever possibly learn and grow and heal to overcome this lasting tragedy.

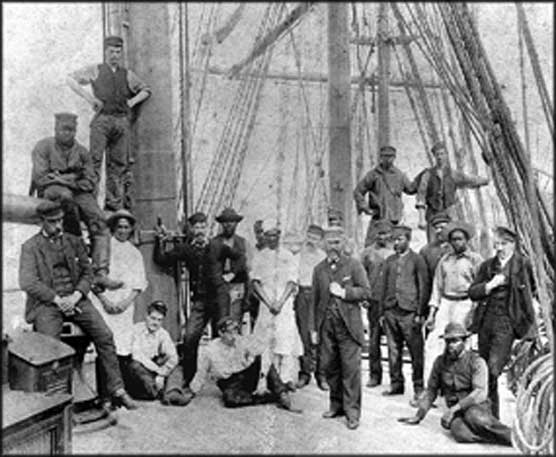

Nantucket’s own history gives a glimmer of hope. Students of the whaling under sail know that the microcosm of the whale ship was a uniquely desegregated bastion in 18th and 19th Century America, the sole level deck of community and a revolutionary degree of equal opportunity. Among whaling crews and throughout the supporting shore-bound industries were to be found people from every race, culture and creed found in the maritime world. It was the only forum where whites worked, hand-in-hand alongside, and even under, people of color. It is one of the reasons why antique scrimshaw is so important, the whaleman’s own folk art documenting and portraying life in this uniquely egalitarian pursuit.

Whether it was the generally undesirable nature of the job, or the tolerant doctrines of the Quakers on Nantucket, the whaling industry early-on welcomed all minorities. Whaling was such a grueling, ill paying and low-status job that able bodied seamen sought berths anywhere else, allowing ample opportunity those normally marginalized to get a foot on deck. Once aboard, whaling provided a chance for African, Caribbean, Native American, Asian and Oceanic whalers to earn a comparable wage and gain a measure of respect. Racism certainly still existed aboard ship of course, but men were paid equally depending on the work they did and blacks could gain status as officers or harpooners if they had the necessary skill and dedication.

An examination of whaling crew lists (for example from the New London area) showed that vessels on average sailed with some ten percent men of color, and a total of about 700 men of color as officers or harpooners during the seven decades between 1819 and 1892 (in an industry that peaked locally between 1835 and 1845 with a total of around 2000 men directly employed).1 In addition, great numbers of minorities also worked in whaling related jobs as coopers, riggers, sailmakers and merchants. The industry brought many immigrants to New England the region as crew members from Hawaii, the Azores, the Cape Verde islands and other locales. In fact, Cape Verdeans whalers are thought to be the first Africans to voluntarily migrate to the United States.

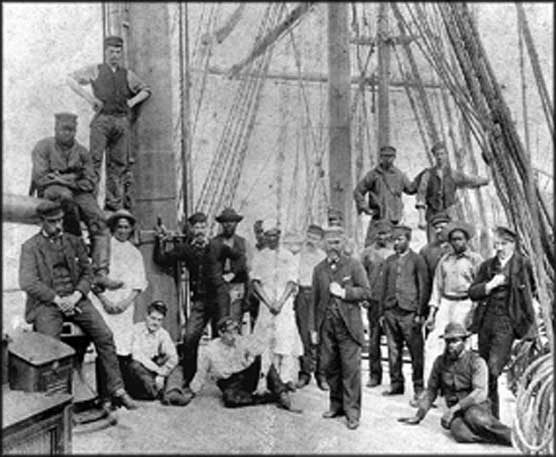

Put this in the context of the times when whites and people of color never worked alongside each other, certainly not as peers, and certainly not for an equal wage. Even more astounding is the fact that blacks and other whalers often rose to rank of boatsteerer (harpooner) or mate, where they would be working above white sailors in the crew. There are even of course examples of black whalers rising to command their own vessels. Most famous is the Nantucket whaleman Absalom Boston (1785–1855), a son of emancipated slaves who advanced in the industry to become the very successful captain of the whaleship Industry with an exceptional all black crew. A well-liked and respected man, upon retiring he worked on behalf of Nantucket’s black community and helped to integrate the island’s public schools.

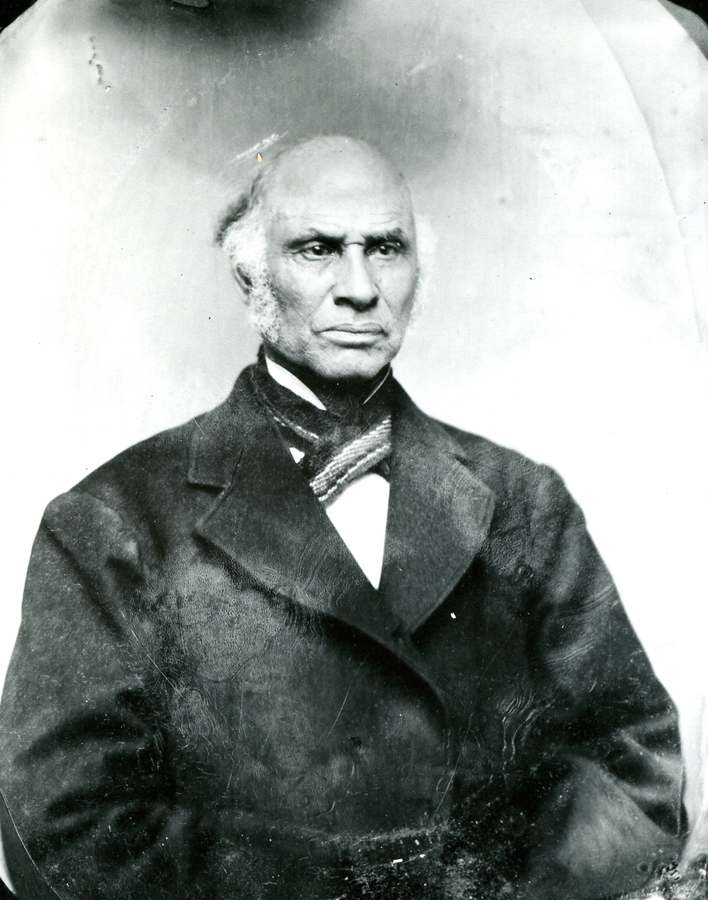

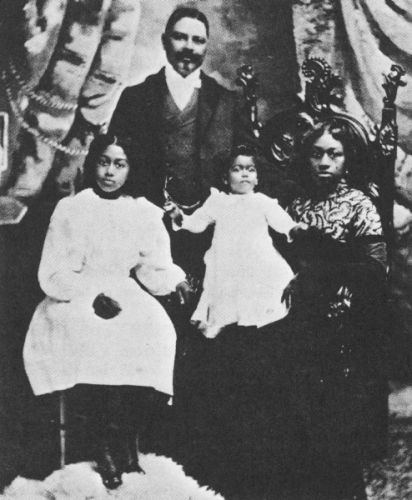

Captain Boston was not alone. Antoine DeSant (ca. 1815-1886) was born in the Cape Verde Islands and made his way to New London, CT sometime around 1830. He sailed on four whaling voyages as a crew member before the mast aboard the whaleship Tuscarora, and was likely involved in nearly a dozen whaling voyages or more, before becoming an officer on the shipping vessel Portland in 1850. Farther south Barbadian William T. Shorey (1859 – 1919) was another whaleman respected for his skill in harpooning and leadership, who rose to become Third Mate of the Boston whaler Emma F. Herriman, and eventually captain of his own vessel commanding a multi-racial crew. As master of the San Franciscan whaling bark John and Winthrop he became known as “Black Ahab.”

Most famous of all was Lewis Temple (1800 – 1854), a former slave from Richmond who moved to New Bedford, became a blacksmith and went on to open his own whaling craft and supply shop, and eventually a harpoon manufacturing plant. Inspired by the native harpoons of Inuit and First Nation whalers he invented the Toggle Iron, a new and improved harpoon which quickly revolutionized the trade and became the new standard harpoon for whaling.

Surely the fact that whaling was the last choice for most sailors was an important factor in allowing people of color the opportunity of joining the crews. Then the reality of a small crew of some 30 or so men forced to be solely self-reliant in some of the most remote and inhospitable seas allowed those with talent and drive to prosper and advance irrespective of their race or origin. But there has to be more to it than just the economics of the labor force. After all there were other comparably dismal industries that were similarly the last choice of a desperate worker, where we did not see as equal an opportunity as in whaling.

The very nature of Quaker philosophy must have been equally important. Their steadfast belief in equality, tolerance and compassion provided the perfect setting for equal opportunity. It clearly was not just profit driven, for where was the monetary gain in their drive behind the Underground Railroad, or their early support for Woman’s Suffrage? Embracing the virtues of equality, tolerance and compassion…perhaps it is possible to learn and grow, to heal and overcome this lasting tragedy.