The nature of a sailor’s life and work made them well suited to create distinctive folk art. Their livelihood required a skill set that included knots and ropework, canvas work and stitching, and of course carving. Most people are more or less familiar with their scrimshaw, models, ships-in-bottles, fancy ropework and macrame, and carved and inlaid boxes and objects. These whimsies all provide a reflection of the sailor’s lives, their cares and concerns, desires and accomplishments. Their history and creation are well studied and documented. In contrast, sailor embroidered wool yarn pictures are surely the least known and understood of all the sailor’s crafts.

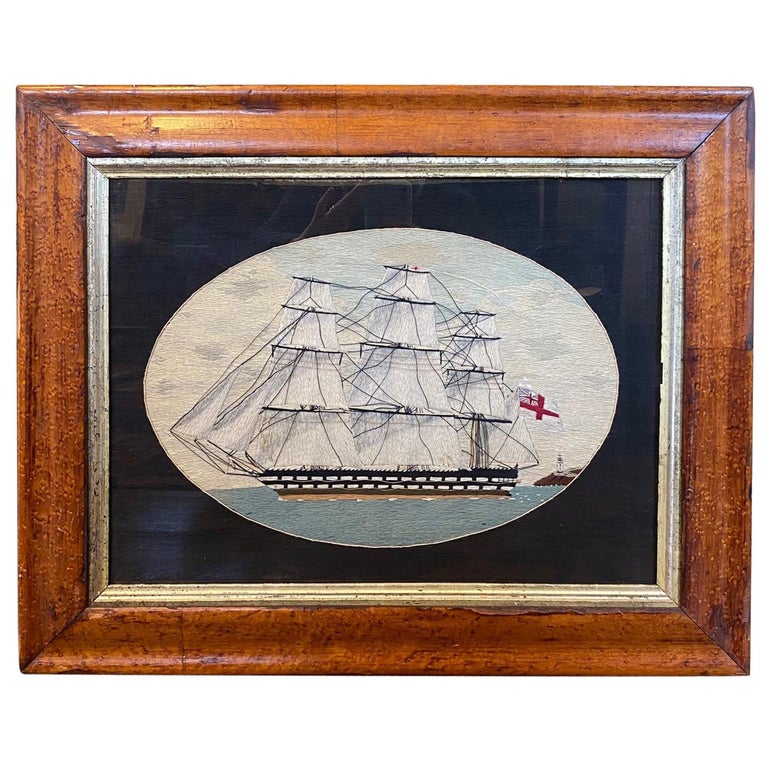

These sailor’s woolwork or “woolies” are most often simple broadside views of ships, especially British warships. We want to ascribe an intimacy, that the sailor is depicting the ship on which he served, but there is rarely any evidence to support this assumption. While sometimes a specific vessel is portrayed, more often we see a fairly simple rendition of a generic ship, or an amalgamation of different ships mulled by memory and imagination. We are used to describing sailor’s folk art as being very accurate, with true and detailed renditions of ships and rigging, but woolies are not engravings, nor is yarn a fine bristled brush – the truth is that most woolies are simple and naïve… delightfully so.

At the same time the composition of woolies can be quite complex with multiple vessels of various rigs portrayed, and may often involve flags, national emblems and coat-of-arms, coastlines and lighthouses, naval battles, fisheries, yachts, shipwrecks, foreign ports, volcanoes, even figures in landscapes (often akin to a “sailor’s farewell”). Some examples become quite fanciful with naïve dis-proportions, charming liberties taken, and whimsical compositions framed within a life ring, porthole or other roundel, or staged between theater curtains or the like.

The woolwork pictures, both simple and complex, are made from pieces of woolen yarn stitched through a fabric backing. The work involved a variety of different stitches: the earliest pieces appear to have used the chain stitch, where each stitch seems to go into the one before and is less than a quarter of an inch long. By mid-century these had evolved into the long stitch, where long strands cover ground quickly on the front and leave very little on the back, saving wool and makes for much quicker work. The adventurous also used cross stitches, applique, darning and the quilting technique trapunto to create raised puffy surfaces. The most fanciful also could include bits of other objects such as photographs, silk, beads, tinsel, sequins and even bone, shell and exotic woods. The backing is typically cotton duck, sometimes linen or other cotton cloth. Despite popular myth sail cloth was rarely, if ever, used due to its thickness.

There is very little literature on sailor’s woolies, and thus most people know very little about them. Unfortunately most were not signed or labeled. A small number might include the name of the vessel, and very few might include the maker’s initials or full name. Nevertheless a fair amount of history has been learned over the years by curators and collectors. These woolies were almost entirely the work of sailors and 99% were British. The consistent subject matter indicates that in particular they were mostly British naval seamen. There are of course fascinating exceptions. There are a small number of British soldier’s woolies, usually depicting regimental colors and emblems coming out of the Crimean War or The Raj. There are also a number that were made by Trinity House lighthouse keepers (more on them later). Very few were made by sailors from America, France or other countries (remember that the depiction of a foreign flag on a vessel does not mean that the picture was made in that foreign country). Amongst the rarest woolies are those that depict fishermen or whalers.

We have also learned that sailors began making these woolworks in the 1830s (perhaps some from the 1820s). The craft reached a plateau by the 1840s and peaked in popularity in the 1860s and 1870s.They decreased in prevalence by the turn of the century. This sailor’s folk art did continue into World War I but then pretty much disappeared. It has been suggested that sailor’s woolwork was inspired by the Chinese embroideries brought home by sailors in the China Trade, but woolies were already reaching a peak of popularity when those export pieces were coming onto the market in the 1840s.

The apocryphal story of woolies is that like scrimshaw they were made by sailors to while away lonely hours aboard ship to help pass the time and stave off boredom. Unfortunately, there is little evidence to support this supposition. The materials employed were not found on board ships, and the techniques were not those used by sailors in their shipboard lives. Furthermore it is clear that most woolies were done by navy men, however Her Majesty’s Navy was not known for allowing much leisure time for the crew before the mast… idle hands and the devil and all that. Consider that a 250 foot ship of the line in the mid-19th Century carried nearly 1300 seamen crammed into very inhospitable quarters, an awful lot of idle hands and tempers to get into mischief. Nelson’s navy was a cruel and demanding task master for the very reason of keeping that horde from getting idle and bored… and mutinous. Not surprisingly it has finally become pretty generally admitted that the vast majority of woolies were not made aboard ships, but made by sailors ashore, retired or otherwise.

We see a lot of folk art created by whalers, and fishermen, and packet sailors and the like, but not so much by navy tars onboard ship. What time they had below (generally only 4 hours between watches) was taken with eating, mending their clothes and forever trying to catch up on too little sleep. If they did manage some idle hours, and resisted the lure of gambling, there was plenty of scrap wood, rope ends and beachcombings to pursue the well documented carving and fancy knotwork. The idea that rough seamen were squeezing a visit between pubs to hit the “sundries and fancy goods” shop ashore to pick their colors and stock up on yarn for the coming voyage is verging on Monty Python territory.

The reality is that from the time of Cromwell’s Commonwealth period until the end of the Napoleonic and American Revolutionary wars the British were engaged in nearly 170 years of unending naval warfare. By the 1820s there were an awful lot of injured and decommissioned sailors adrift on shore and the crown didn’t know what to do with them. The relative peace led to few warships being outfitted, and the rise of steam engines was inevitably putting an end the age of sail. Unemployment soared along the waterfronts and wages plummeted. The naval hospitals were overflowing, and every port had more than its share of begging “Chelsea Pensioners.”

Research has found that during this period British naval hospitals began teaching sailors woolwork… the world’s first physical and occupational therapies. After mastering the basic patterns provided, those sailors that took well to the new craft gave vent to their imaginations and stitched the fanciful pieces that have come to fascinate us. Beyond the therapeutic value, the craft also gave these sailors a means of earning a few shillings. Such a source of income, meager as it may have been, would have been of great comfort to the impoverished beached sailors. While the romantic myth holds that these were made as souvenirs of a voyage or as a gift for a loved one, it is more likely that most woolies were folk art made for sale. Old price labels have in fact survived on some examples.

Along this line are woolies made by Trinity Houses sailors. The Trinity House Corporation is the official authority for all lighthouses in Great Britain, and also responsible for the provision and maintenance of other navigational aids such as lightships and buoys, as well as providing deep sea pilotage (founded in 1514 with the formal title of The Master Wardens and Assistants of the Guild Fraternity or Brotherhood of The Most Glorious and Undivided Trinity and of St Clement in the Parish of Deptford Strond in the County of Kent). During the latter 19th Century the keepers of lighthouses and lightships while on station made exceptional boxes with fancy wood inlays, often featuring sloops, lighthouses and other nautical symbols of the period. The keepers sold these boxes directly to the captains of sailing vessels using Trinity House services. Surviving examples are highly sought, and include still banks, valuables boxes and lap desks. It has been reported that many keepers also made woolies – we sometimes find woolies with ships sailing past a lighthouse, with both flying the Trinity House ensign. The tradition is somewhat analogous to the Nantucket Lightship Baskets that were made aboard ship for sale to islanders and visitors alike to augment the sailor’s meager wage.

Later yarn embroidered pictures made by home hobbyists will sometimes appear on the market, often copying the form and manner of the antique woolies, but these are much simpler, appear pretty lifeless, and quite easy to discern. One must of course beware of potential fakes, new embroideries deliberately made to appear antique, but even these are most always easy to identify. New work does not share a 19th Century sailor’s perspective and detail. The honest untutored naivety of the originals is very difficult to fake. Especially telling is the lack of insect damage to the wool, and the unmistakable century of fading when the front is compared to the reverse.

True antique sailor’s wool works are an enchanting folk art that provide a fascinating glimpse into their lives, showing us their pride and toil, what they worked with and for what they risked life and limb. We see the use of the simplest materials to create images that are charming at the least, wild and exciting at the best. And often there is a very surprising artistic sensibility: likely due to the crude and limiting nature of the materials, the rendering especially of the sea and sky can appear quite boldly modern to our eyes.

What do collectors look for in woolies? What factors affect the desirability and value of any particular work? While some would say the first and most important consideration is condition, for me it is the artistic composition and complexity of design. I am swayed by the more elaborate and intricate, the more images involved, the more sophisticated and nuanced the depiction, and the greater (or crazier) the naïve folkish vision. Visual appeal is key, with the use of color so important, whether it be soft and subtle or bold and vibrant.

Condition is of course important: the piece must have stability and be presentable. But keeping in mind the fragile and perishable materials involved, I expect there to be some fading, and usually some evidence of moths visiting in the past. And a frayed line or two in the rigging does not ruin my day. It is all a matter of degree: the finer the condition the better, but we are realistic and forgiving. Does size matter? In general most woolies are no more than 24 inches wide, and the value goes up as the work gets larger. On the other hand, smaller woolies can be unusual and very appealing, and so may very well hit above their weight in value.

A final consideration is historic significance. Most woolies are anonymous views, so any identification of the ship or scene portrayed will certainly add interest and desirability. Likewise, if the sailor can be named, or the time and place of the work specified, interest is piqued. And if the image is rare or unusual in a woolwork, such as a whaling scene, life-saving scene, or other dramatic action, the value is understandably enhanced. At the end of the day, as with all folk art, the most desirable piece is the one that grabs your attention and excites your imagination.

For additional reading:

www.antiquesandfineart.com/articles/article.cfm?request=311

www.barbaraleighantiques.com/2016/01/05/folk-art-sailors-woolworks-or-woolies/

www.richardgardnerantiques.co.uk/antique-sailor-woolwork-pictures-or-woolies/

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trinity_House

Pope, Dudley. 1981. Life in Nelson’s Navy. Naval Institute Press.

Woodman, Richard and Andrew Adams. 2013. Light Upon the Waters: The History of Trinity House 1514-2014. Trinity House Publications.