A MOST UNUSUAL HARPOON

This article first appeared in the Nantucket Historic Association’s Historic Nantucket Magazine, Fall 2020 (v.70 n.2)

nha.org/research/nantucket-history/historic-nantucket-magazine/25302-2/

It seems that in the eyes of the Yankee whalers, a whale was a lot like a mouse and they were forever trying to invent a better mouse trap. Whalemen were like all fishermen in begrudging the one that got away. A quick perusal of logbooks shows that many whales did in fact get away after being darted by a harpoon. In light of this, it is not surprising that the pursuit of the whale fishery gave rise to many attempted improvements in the tools of the trade: there were eventually at least 23 different types and 34 unique U.S. patented harpoons.1 Some of these, believe it or not, actually were improvements.

One of the oddest of the harpoons was the little known (and rarely seen) Humpback Iron. This device was a greatly over-sized version of the improved toggle iron. It follows the design of a standard hand darted harpoon and could not possibly be fired from a gun. But just a quick glance at one in a museum immediately shows the mystery…this iron was too large and heavy to have been effectively thrown. The surprising answer does not disappoint and reveals the ingenuity (and desperation?) of the old whalemen.

The humpback was one of the five species normally hunted by the Yankee whalers. It was the least desirable of prey since it sank about half the time after being killed.2 In later years after the collapse of whale oil prices and baleen became the driving commodity,3, 4 the humpback became even less desirable as its baleen was considered useless for commercial purposes.2, 3 The pressures of the Revolutionary War forced Nantucket whalers to rely on short, quick cruises in nearby waters, and since the right whale population had been depleted, out of desperation they were forced to chase humpbacks in large numbers.5, 6, 7, 8 New England whalers in small shore-based operations throughout the Gulf of Maine in the mid- and late-nineteenth century also had to resort to humpbacks as all other whale species disappeared and the menhaden oil fishery waxed and waned.5, 9, 10, 11

Since at least half of the humpback whales captured promptly sank, the fishery was run (in Maine parlance) as a “shoot and salvage” operation. Small, fast schooners carrying no more than two whale boats chased the whales, which despite their speed could be caught and killed with relative ease now with the advent of shoulder guns and bomb lances. The problem lay with so many whales sinking that now needed to be recovered off the ocean floor. In order to have any hope for success, the humpback fishery had to be pursued in shallow waters less than forty fathoms in depth,12 and specialized recovery methods needed to be devised.

Simply trying to raise the whale by hauling back on the original harpoon line would not work: the small toggled head would pull out. Yankee ingenuity offered the solution of a specialized recovery harpoon—the “Humpback Iron”—with a greatly enlarged toggle head (in the order of ten inches as opposed to the standard five to six inches) and

Humpback Harpoon that hung for many years on the door of the Four Winds Gift Shop on Centre Street, which had been a non-whaling blacksmith’s shop until about 1950.

a much thicker and stronger shank (from one half to nearly a full inch in diameter as opposed to the normal average of about three-eighths inch). The harpoon was rigged, of course, with a much thicker and stronger whale line.1, 13

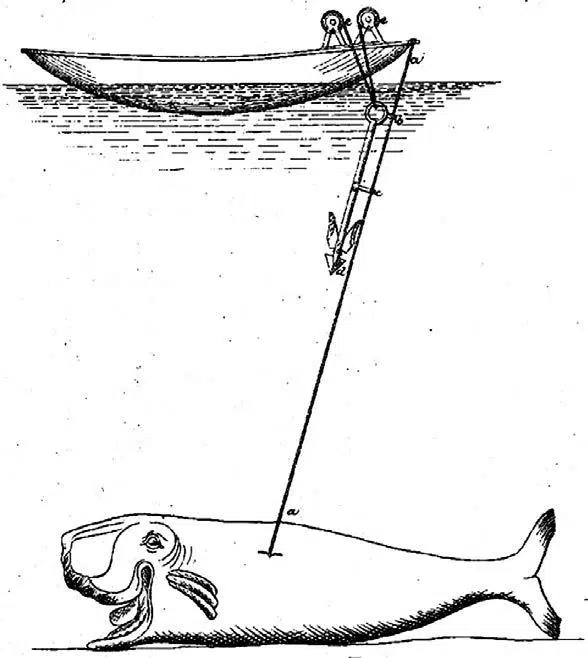

In use, a humpback iron was darted into the whale after it was taken with a traditional harpoon. If the whale sank before this could take place, then the carcass had to be harpooned on the bottom of the sea in an attempt to raise it! This was accomplished by mounting the recovery harpoon atop a long shaft from a cutting-in spade, attaching a heavy chunk of pig iron near the head (about 30 pounds or so), and a couple of iron hoops fastened along the shaft; to use, the original darted harpoon line leading up from the carcass was rove through the hoops, then the weighted recovery iron was sent traveling along the line to the bottom in the hope of driving firmly into the carcass. After a wait of a few days, the gases of decomposition would make the whale more buoyant, and the heavy line of the recovery iron would be slowly hauled back to raise the whale.1, 13, 14

Never wanting to “leave well enough alone,” in time there was an attempt to make an improvement on the Humpback Iron, and in 1862, Thomas Roys of Southampton, Long Island, patented an apparatus for Raising Dead Whales from the Bottom of the Sea. This so-called “Whale Raiser” was a massive affair altogether: a swivel barb harpoon that was ten feet long and weighed two hundred pounds, having a huge triangular head with two cutting edges backed by two very long pivot barbs, two guide hoops, and ending in a large ring in place of the normal open socket. In practice, a small codline was attached to this ring; after fastening to the sunken whale, this line was used to pull a larger line through the ring, and then in turn a larger hawser, which was to be hauled back by the ship’s windlass.1, 13

Roys tried hard to impress the whaling fleet with his new invention, and throughout 1861 he ran advertisements in the New Bedford bimonthly Whalemen’s Shipping List, and Merchant’s Transcript, which claimed,

This instrument will attach any number of lines to whales that are dead on the bottom, and can be furnished for forty dollars; it can be done in anything less than one hundred fathoms of water. If it fails to give satisfaction if tried, the money will be refunded at termination of the voyage. Apparently Roy never had to give a refund, because it does not appear that his campaign was successful. Yankee whalers were not impressed with an unwieldy forty-dollar contraption when they already had an inexpensive Humpback Iron to do the job. There is no evidence that a single one of his devices was ever used.1, 14 In fairness, there was not much demand—even the recovery harpoons were not in widespread use—so that today they are among the rarest antique harpoons. Most people, even seasoned collectors of whaling items, have never seen a Humpback Iron. However, you can examine one right here on Nantucket at the Whaling Museum, where there is a fine one on display in their whaleboat.

References Cited:

- Lytle, Thomas G. 1984. Harpoons and other Whalecraft. Old Dartmouth Historical Society.

- NBWM. 2020. Overview of North American Whaling. https://www.whalingmuseum.org/learn/ research-topics/overview-of-north-american-whaling

3. Davis, Lance E., Gallman, Robert E. and Karin Gleiter. 1997. In Pursuit of Leviathan: Technology, Institutions,

4. Davis, Lance E., Gallman, Robert E. and Teresa D.Productivity, and Profits in American Whaling, 1816–1906. University of Chicago Press. 4

5. Hutchins. 1988. The Decline of U.S. Whaling: Was the Stock of Whales Running Out? The Business History Review Vol. 62, No. 4 (Winter, 1988), pp. 569-595

6. Allen, G. M. 1916. The Whalebone Whales of New England. Mem. Boston Soc. Nat. Hist. 8(2):105–322.

7. Macy, O. 1835. The history of Nantucket. Hilliard, Gray, and Co., Boston.

8. Starbuck, A. 1878. History of the American whale fishery from its earliest inception to the year 1876. In Rep. U.S. Comm. Fish Fish. 1875–76, App. A.

9. ________ . 1924. The history of Nantucket County, Island and town including genealogies of first settlers. C. E. Goodspeed & Co., Boston.

10. Clark, A. H. 1887a. History and present condition of the [whale] fishery. In G. B. Goode (Editor), The fisheries and fishery industries of the United States. Sect. V, History and methods of the fisheries, Vol. II, pt. XV, p. 3–218. Gov. Print. Off., Wash

11. Mitchell, E., and R. R. Reeves. 1983. Catch history, abundance, and present status of northwest Atlantic humpback whales. Rep. Int. Whal. Comm., Spec. Iss. 5:153–212.

12. Randall R. Reeves, Smith, Tim D., Webb, Robert L., Robbins, Jooke and Phillip J. Clapham. 2002. Humpback and Fin Whaling in the Gulf of Maine from 1800 to 1918. Marine Fisheries Review 64:1-12

13. True, F. W. 1904. The whalebone whales of the western North Atlantic compared with those occurring in European waters with some observations on the species of the North Pacific. Smithson. Inst. Press, Wash., D.C. (1983 repr.).

14. Brown, J. T. 1887. The whalemen, vessels and boats, apparatus, and methods of the whale fishery. In G. B. Goode (Editor), The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States. Sect. V, Vol. II, pt. XV, p. 218–293. Gov. Print. Off., Wash.

15. Smithsonian Institution. On the Water. 3: Fishing for a Living 1840 – 1920. https://americanhistory.si.edu/ onthewater/exhibition/3_7.html